On a rare trip to a local LCBO to buy wine recently (I try to buy direct), I watched and listened as a young consumer asked an employee about sustainable wine.

“I’m looking for something that’s environmentally responsible with no i-cides,” she explained. “No pesticides, no herbicides, no fungicides – basically, no chemicals. Do you have an organic section?” she asked.

“No,” sighed the employee. “We don’t. We probably should – and I’d put it right here” she said, indicating the customer should follow…. “but right now we don’t.”

“Okaaaay,” said the slightly frustrated customer.

“I mean, we do have quite a few producers of organic wine,” the employee continued. “But you have to walk the aisles and look for them. Look for a little black and white leaf. Or sometimes there’s a sign that says organic,” she said, quickly removing an upside-down organic sign.

“Ok, how about natural wines?” the customer persisted.

“What are those?” asked the employee.

(“Sigh”….said I, to no one in particular.)

Wine and the changing climate of Sustainability

As someone who thinks long and hard about the impact of my purchase decisions, I was both encouraged and dismayed by this exchange.

Here we had a consumer who cares deeply about her ecological footprint, trying to buy planet-friendly wine, only to be thwarted by the retail environment. The LCBO talks the sustainability talk, but they clearly fell short on ‘the walk’- aka employee and store-level environmental education. At least at this location.

The reality is, wine farming and wine production contributes to global greenhouse gas (GHG) production, deforestation, water consumption and biodiversity loss. All those bottles, closures, labels, cardboard packaging and transport exact a heavy carbon toll. With responsible, sustainable practices, those impacts can be mitigated, and there are many wineries actively working to repair agriculture’s broken relationship with the land.

As my climate action literacy improves, my wine buying behaviour changes. I’m supporting small, responsibly produced organic, biodynamic, regenerative winegrowers, using natural and minimal intervention methods in the cellar.

And I’m clearly not alone. A recent workshop I attended at a local natural wine shop in Toronto called Grape Witches (ahem: standing room only) tackled some of these issues.

If you want to avoid i-cides – as the mystery shopper at the LCBO clearly did – and support wine brands tackling the climate crisis, what do you need to know? Is it best to buy organic wines, natural wines or something else entirely? And what vineyard and winemaking practices are associated with reduced carbon emissions and environmental stewardship? Each time we buy wine we have a chance to be the change!

According to a joint McKinsey/Nielsen report from January 2023, consumers want “sustainability” – real, true, unvarnished sustainability – to be the new business baseline, whether you’re a brand or retailer. Young people care deeply about these issues, as you can see in research studies here, and here.

So, lessons learned for the provincial monopoly? Try harder. Increase your store-level sustainability education. Make environmental literacy part of the retail, wine buying experience. QR codes, better signage, environmental wine ambassadors. For starters.

READY TO LEARN??

Below is a ‘glossary’ of what I would call environmental wine making philosophies. They’re not very well understood by consumers, but tell you everything you need to know about environmental impacts. They run the gamut from “fuck it” to tracking the phases of the moon. Each one of these production methods could be a book – but hopefully it’s a start at understanding what’s actually in your glass.

A WINE METHODS GLOSSARY

Conventional Wines

Ok – I’m making up this number because despite my research efforts, it’s impossible to find an accurate data point here, but fair to say conventional wines make up 90+% of the wines in the market. For the record, my meagre cellar is full of conventional wines. It’s what most people in my age group have grown up drinking.

“Conventional” wine is a broad-spectrum term for a broad spectrum of wines that are produced using the full suite of viticulture tools available to ensure a wine crop’s success. This includes synthetic herbicides, pesticides, fungicides, insecticides and chemical fertilizers.. In the cellar, it means sulphites to control unwanted bacteria and oxidation (conventional wines can have up to 400 ppm of SO2. vs zero for a natural wine), sugars, acidity enhancers, catalogues of additive options, fining and filtering agents to ensure clarity and consistency.

Smaller, artisan producers and high-profile fine wine producers might use very few of these farming aides and interventions, and only as required to ensure the success of their crop.

Industrial, corporate, big brands, on the other hand, often employ ‘whatever-it-takes’ toolbox of practices to ensure a consistent crop and consistent wine profile. That’s because maximizing profits is overwhelmingly the goal.

Industrial producers generally rely on chemically-intensive viticulture (which compromise soil and employee health & pollute streams and river systems), plough their soils (releasing GHG’s), irrigate (using often scarce water resources), use diesel tractors and mechanical harvesting machines (more CO2 emissions, compacting soils and shredding soil fungal networks), add commercial/manufactured yeasts (to add specific flavours) and a whole slew of additives (colourants, flavour enhancers, tartaric acid, etc.) and technical wizardry (reverse osmosis, micro-oxygenation, de-alcoholization, etc.) to produce wines that offer a consistent profile year to year.

Ultimately, the goal is to control nature. From a climate change perspective, the impacts of this type of winemaking can be profound.

If you want to understand the environmental practices of a producer, start by googling the brand. Look for an earth or vineyard or about-us tab, and see if they share a farming philosophy, or better still, environmental or sustainable third-party certifications. If you don’t see that, dig through specific winemaking technical notes in the Wine (for-Sale) tab.

Above all, fine-tune your BS metre, because there’s no end of greenwashing in wine these days. Everyone loves nature; everyone pays homage to the next generation. An important point to make here: for wine consumers who are price-point sensitive – and that’s many – conventional wines fit the bill.

Organic Wine

Organic wine production is primarily concerned with the use of synthetic chemicals in the vineyard. Grapes are grown without the use of herbicides, fungicides, pesticides and chemical fertilizers. Organic winegrowers argue chemicals destroy the flora, fauna and rich microbial life of the soil and can be harmful to employee health. They also mask the terroir of each vineyard and encourage desertification (land degradation) and soil loss.

Organic farming is responsible farming, and is the chosen method for artisan, handcrafted winegrowers looking to make wines without artifice. The many ecological benefits of organic practices include healthy soils, healthy waterways, biodiversity, and a safe home for bees and other beneficial insects.

Instead of chemicals, organic winegrowers use natural products throughout production (although the permitted use of copper sulphate as an anti-fungal, is a huge point of contention).

Cover crops are the key organic tool here. By keeping soils covered and having diverse living plants feeding soil microbes, cover crops can help reduce soil compaction, the need for fertilizers, improve water filtration and reduce pest and disease pressure.

In the winery, organic wines don’t see additives, flavourings or preservatives (only minimal sulphur). Instead, the final product reflects a true and honest interpretation of the soil, vines and vintage.

The tricky part with Organics is in the labelling. Each country has its own list of acceptable third-party audited, organic certifications. Canada has its own certifications and accepts many US and international certifications (equivalency agreements). You can see Canada’s accepted certifications here.

Further complicating matters, many farmers and winegrowers aren’t certified but their wines may be produced using organic practices.

In the United States, organically farmed grapes must be made into a wine with zero added sulphites to receive the USDA organic seal (note: naturally occurring sulphites occur as a by-product of fermentation and will still be present.)

Since the vast majority of organic wines with organically farmed fruit have some added sulphites, we typically see ‘Made with Organic Grapes’ on the label, instead of ‘Organic Wine.’

In Europe, however, wines can be labelled organic and contain added sulphites… just to add to your confusion.

Regenerative Wine

There’s a lotta buzz around regenerative agriculture and regenerative winemaking, these days. Regenerative agriculture is very much about being attuned to subtle changes in the soil, vines and grapes.

It’s labour intensive, seriously hands-on, and promotes dry farming (the flavour and sustainable gold standard), as I learned when I interviewed the incredibly resourceful Jason Haas at Tablas Creek Vineyard – a California winery in Paso Robles that was the first to be Certified Regenerative.

From a climate change perspective, regenerative viticulture tracks the environmental impact of grape growing by actually measuring carbon capture and microbial life improvements in the soil.

Central to regenerative wine growing is reducing a vineyard’s carbon and water use footprint with an end goal of a winery that’s carbon neutral or even carbon negative.

From a farming perspective there are a few key pillars, all of which directly support soil health:

- no-till or minimal tillage (ploughing) to keep carbon in the ground (carbon sequestration) and reduce GHG emissions

- keep the ground covered (and keep living roots in the soil as much as possible) by employing a site specific and regionally appropriate mix of cover crops

- use biological compost – green manure (aka cover crop), vine clippings, pomace (pressed skins, seeds, stems), biochar ….instead of using chemical fertilizers which release nitrous oxide (a gas that is 300 times more harmful to the climate than carbon dioxide)

- including a diverse mix of plant and animal species, so the vineyard is less about monoculture (increasingly a ‘dirty’ word). In other words, moving away from just growing grapes, to include a healthy mix of biodiversity. This means cover crops, hedges, trees, shrubs, fruits and vegetables with yummy nectar that attract pollinators and beneficial insects. From a terroir perspective, a mix of plants and animals adds a delightful menu of vineyard-specific yeast flavours

- the importance of integrating animals – sheep, livestock, chickens – to help with fertility, nutrient cycling, weed management, pest control and soil compaction. Natural weeding means eliminating tractor passes.

- Regenerative farming – both in practice and certification – acknowledges human rights, providing economic stability and fairness for workers

So, you’re probably starting to see overlap with these practices. And, as with organics and biodynamics, many wine growers use regenerative practices but are not certified.

Wine critic Esther Mobley of San Francisco Chronicle writes “Regenerative farming refers to a set of practices that are distinct — and, arguably, more rigorous — than those encompassed by more familiar sustainability buzzwords, like organic and biodynamic.

By incorporating compost, cover crops, grazing animals and more, it reaches toward a single goal: to use agriculture to reverse, rather than exacerbate, the effects of climate change.”

- Certifications: Regenerative Organic Alliance – ROC, Quorum Sense (New Zealand),

Biodynamics

Biodynamics is a global ‘organics plus’ practice originally espoused by Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner.

Biodynamics incorporates a holistic approach to the land, embracing all the plants and creatures on it (versus the seek & destroy mission of chemical applications….a point shared by the brilliant Jean-Michel Comme when he was at Pontet Canet). Steiner created the concept of biodynamic agriculture in 1924 in response to synthetic fertilizers’ growing death-grip on farmers.

A key insight of the biodynamic movement is that soil is the basis of all life. Accordingly, all practices seek to build the resilience of the vineyard and make vines more resistant to pathogens and pests. Everything added to the soil must come from living things – either the plant kingdom or the animal kingdom. If you see horses in a vineyard, chances are that’s a biodynamic winemaker.

The vineyard is viewed as a ‘closed-circle’ and fertility practices include a series of compost and homeopathic-like preparations that include dung compost spray from buried cow horns – for deeper root growth and soil vitality – and ground silica to attract sunlight, and encourage photosynthesis and the ripening process. Sprays and natural preparations incorporating plants like stinging nettle, yarrow, chamomile, horsetail are added to ward off pests and disease.

It’s important to note, biodynamics in its original incarnation was a spiritual practice, aligned with the cycles of the moon and astrological influences. Planting, pruning and harvesting ideally aligned with the lunar cycle.

Whatever people think of the stranger aspects of the biodynamic philosophy, farmers worldwide, swear by the results. A dearth of evidence-based research aside, winemakers claim a purer, heightened expression of terroir in the wines, and wines from biodynamic vineyards are consistently regaled for their energy and life-affirming aromatics and flavours.

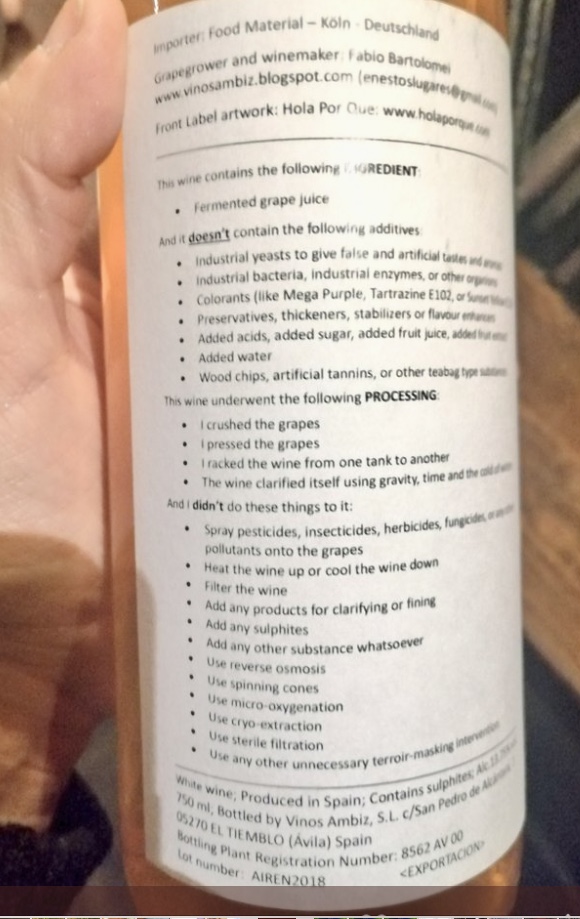

Natural

Natural wines – or low-intervention wines – have become a bit of a cultural phenomenon.

I wrote about natural wines a few months’ back, profiling two respected and utterly delicious wines – Scout Vineyard in BC’s Okanagan and Martha Stoumen from Sonoma County – and the queen mother of natural wines, Isabelle Legeron.

When it comes to natural wines, there are wines that are:

- simply made: 100% organic grapes, fermented into wine. Nothing added, nothing taken away

- ‘#natty’ – high funkability factor, natural yeasts, winemaking that pushes the boundaries by incorporating little-known varietals, hybrid grapes, herbs, fruit, and sulphite free

- made as naturally as possible, and fall somewhere in between

Old-is-New

Before there were conventional wines, there were natural wines – wines made without any chemicals or additives. Natural winemakers were originally identified with a paysan past. The French word “paysan”, translates to peasant, but in reality, these were hard-working farmers, living off the land, making wine as simply as possible and mostly as an accompaniment to a meal.

#Natty winemakers have embraced an old-is-new approach. They’re equal part low-intervention (low to no sulpher, unfined, unfiltered), package design geniuses and rare grape hunters. Grape Witches, a local Toronto Natural Wine grape store – describes this adventurous spirit as the “freakiness” factor. Well-made, clean wines – but with as much barn-yardy, compost, underbrush funk – as you’re up for.

Honestly, freak factor aside – I haven’t had a single natural wine I wouldn’t buy again. They’re consistently fresh, bright, with deliciously precise fruit and herbal notes, and I encourage everyone to visit their local natural wine shop or bar to give them a try. But, per my intro, you won’t find them at the LCBO.

The downside to natural wines? There is no certification in any market. At least not yet. Old and new world winemakers claim to use natural methods in the vineyard (no chemicals, compost, hand-picking) and low-intervention practices in the cellar (minimal sulpher, wild yeast fermentations, bottled unfined and un/minimal filtration), but, without a third-party cert, it all comes down to the integrity of the winemaker and producer.

RAW wines, you ask? RW is a touring wine fair celebrating natural wine and transparent, full-disclosure winemaking. Isabelle Legeron started the movement shortly after her winegrowing father died of cancer from chemical exposure. Ultimately, she wants wine consumers to think about the environmental impact of wine. There’s been push-back from some “purists” in the natural wine industry that the RAW fair profit motive is corrupting the essence of natural winemaking. That debate aside, I’d argue it’s fabulously exciting to see so many young consumers supporting environmentally conscious winegrowing.

Polyculture

A really smart guy in the wine-ish industry – Brian McClintic – thinks the hero worship of wine as a single grape, must go.

In re-thinking terroir, he argues that the premise that one grape should be the lone spokesman for a vast eco-system of plant life is foolhardy, and that the vibrancy of life, the strength of a place’s signal cannot be fostered in isolation.

For many of today’s young winegrowers, monoculture is a largely extractive, environmentally harmful practice (um, see conventional wines), short-changing the concept of terroir and the possibilities of wine. Brian McClintic’s online wine subscription service, Viticole, represents farmers making wine with an ‘ancestral’ mindset (more paysans!).

Polyculture celebrates biodiversity by adding orchard fruits and herbs and trees and a diversity of plant life to grape farming, and ultimately to wine. Sometimes peaches and grapes are co-fermented, or apples and wine, or herbs and grapes. Whatever the mixed fruit blending looks like, it represents a collaboration with nature, which sounds pretty tasty to me.

Permaculture (Permanent Sustainable Agriculture)

Sometimes described as cover crops on steroids, permaculture is about giving nature free rein. Ultimately, it’s the most eco-friendly, regenerative and responsible form of grape farming, keeping vast stores of carbon in the ground. Grapes grow alongside native plants in the vineyard, all to nourish the soil and pay homage to nature’s possibilities. No chemicals, no-till, no diesel. Thinking hippie winemakers? Or perhaps winemaking that encourages biodiversity, protects soil structure, reduces erosion, and creates healthy, microbial communities.

Sustainable Wine Production: Separate Certifications are provided for Vineyards and Winery

Sustainable wine production focuses on the long-term health of the vineyard, the surrounding ecosystem, the business and the surrounding community.

Certifications abound, and some winemaking communities like California have a variety of sustainable certifications, all with varying levels of focus, reporting and oversight (see above).

Whether its Napa Green, Lodi Rules, SWNZ from New Zealand, the ISO14001 Environmental System, Sustainable Winegrowing Ontario, these Sustainable third-party certification programs all offer a framework that promotes responsible environmental practices with a view to decarbonizing the wine industry and a carbon neutral or net zero transition.

Many of the practices build on organic, biodynamic and regenerative farming and – in varying degrees – include the use of cover crops, composting, integrated pest management, sustainable land use, preservation of nature and biodiversity, ensuring wildlife habitats, and conserving water and energy.

In the cellar, sustainable practices includes the move to eco-thoughtful wineries: the production of clean, renewable energy, use of energy efficient recycled bottles and alternate glass formats (bag-in-box, cans, cardboard bottles, kegs), green transport, rainwater collection, recycling water and waste, CO2 capture from fermentation, inert gas use vs water for barrel cleaning, renewable business operations (travel, electricity, vehicles, offices), LEED wine production mindset (gravity vs pumping), basically, putting the full chain of winery activities under the carbon footprint microscope.

On the business side, a social justice and social responsibility mindset that includes a living wage, rigorous employee health and safety standards, a diversity equity and inclusion mindset, and – critically – employee education around sustainable land use and fighting climate change. They also ensure the agricultural impacts within the community are respected.

Of course, not all certifications are created equal. Some programs are in their infancy, others are well-established with high levels of local winery participation. Some have robust annual C02 reporting expectations, and limit specific chemical use, others are less stringent.

Some final thoughts…..

After that little pep talk – gotta say – the most recent (March 2023) Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report. makes for grim reading. The IPCC notes that despite expanded business efforts and government policies, global GHG emissions continue to rise.

In the wine sector, we’re definitely seeing a growing commitment from wine producers fighting climate change.

Many are changing vineyard practices to focus on healthy soil, carbon sequestration and regenerate the environment. In the wineries, they’re reducing energy consumption, introducing clean energy, rethinking packaging and transport, and reducing – and measuring – their carbon footprint. For starters. There’s greater transparency and some kick-ass communities taking real, authentic sustainable action. In my next post, I’ll introduce you to some of them.

In the meantime, go forth, research and pour. And like our local LCBO environmentally conscious heroine, think about supporting winegrowers who are on the right side of the planet. Clearly, we all have serious work to do.

And for those who made it this far, here’s a beautiful example of regenerative farming and why nature beats pesticides every time.

Another great read for amateurs like me, Debbie …. I’m certainly getting an education. Such interesting angles to consider. Thanks!!

LikeLike

Thanks Liz….as always, it’s all about the research! lol

LikeLike